Also known as North America’s giant, the California Condor is the largest flying bird on the continent. Unlike hunters built for speed or stealth, condors are specialists in endurance—soaring for hours on thermals, scanning vast canyons and coastlines for carrion. Once nearly lost forever, they are now symbols of survival, slowly reclaiming the skies.

- Length: 43–55 inches (109–140 cm)

- Wingspan: 8.5–9.5 feet (260–290 cm)

- Range: Historically spread across much of western North America, now found only in limited reintroduction sites in California, Arizona, Utah, and northern Baja California.

What to Look For

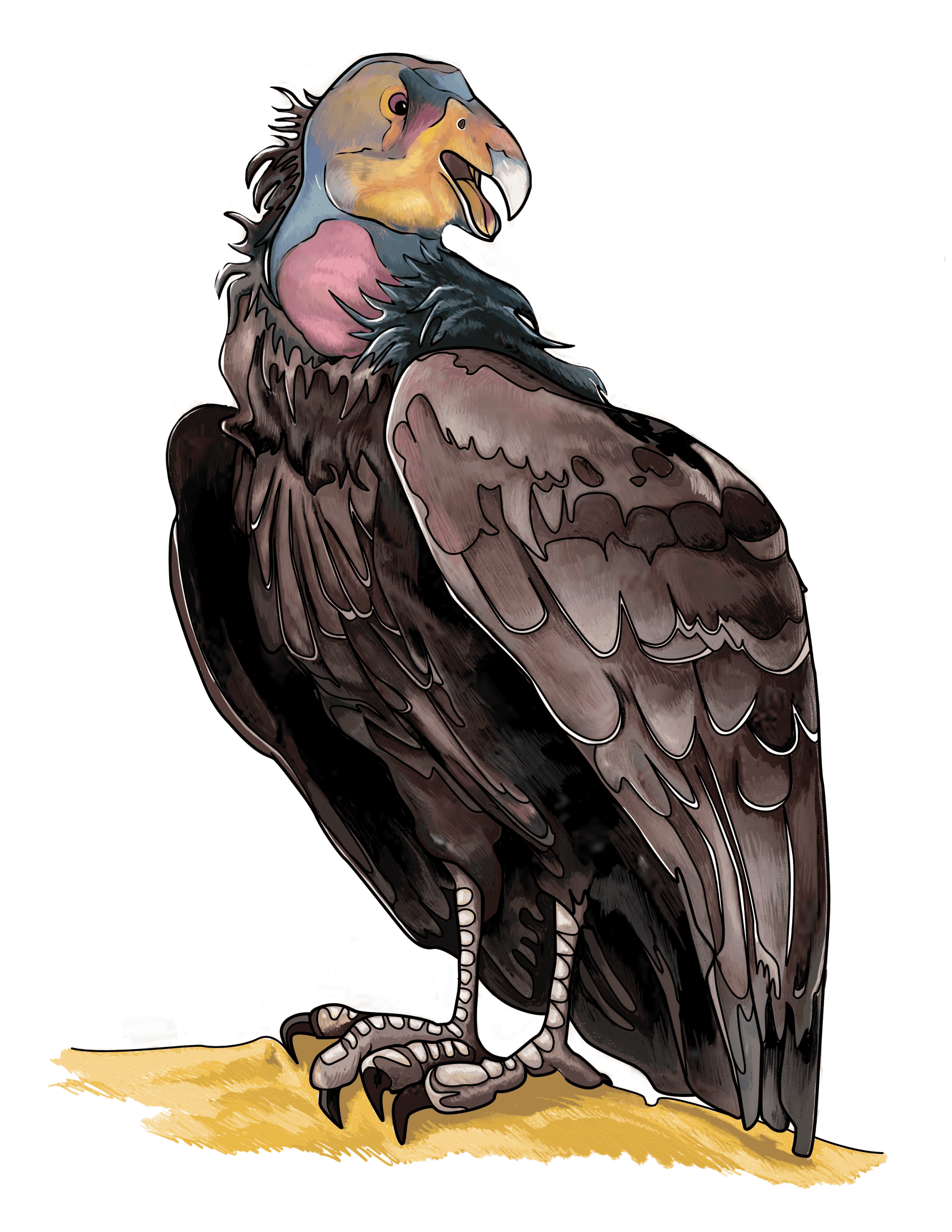

The California Condor is a bird that commands attention by sheer scale alone. With wings stretching nearly ten feet across, it dwarfs hawks, eagles, and even most vultures. In flight, the wings appear long and rectangular, the primary feathers spread like fingers at the tips. Against the sky, adults show a stark contrast: black wings with brilliant white linings that flash when they bank. Juveniles start with mottled gray underwings, gradually whitening as they mature, a slow shift that mirrors their long road to adulthood.

The head and neck are bare, a wash of pink, orange, or yellow depending on the light and the bird’s age. At first it looks harsh, but like the Turkey Vulture, this adaptation is perfect hygiene for a bird that spends its life inside carcasses. Perched, the condor’s size is even more striking. They look heavy and lumbering on cliffs or ledges, their hunched forms giving little clue to the effortless grace they show once airborne.

Comparisons with Turkey Vultures are inevitable, since both share the sky over western canyons. But condors are unmistakable once you learn the differences. They soar with steadier wings, without the rocking, side-to-side wobble that makes Turkey Vultures look unstable. Their size is the giveaway too: when ravens, hawks, or vultures drift alongside them, the condor looks colossal, a shadow that fills the sky.

Behavior & Flight Style

California Condors are the definition of endurance fliers. With wings as broad as a small aircraft, they can spend hours aloft without a single flap, riding columns of warm air that rise along cliffs and canyon walls. Their flight is steady and deliberate, lacking the rocking wobble of Turkey Vultures or the quick, powerful strokes of eagles. To watch one drift overhead is to see patience perfected — an ancient rhythm honed for conserving energy while scanning enormous landscapes below.

On the ground, the difference is striking. Condors can look awkward, lumbering across ledges or shuffling with heavy steps around a carcass. Yet even in these moments, their sheer presence is commanding, a reminder of their role as top scavengers of the American West. At feeding sites, they gather in loose groups, often yielding to dominant birds but always part of a social order that keeps the meal moving.

Their daily routines are tied to the sky. At dawn, they launch from cliffs or high roosts, spreading those massive wings to catch the first thermals of the day. By afternoon, they may range dozens of miles in search of food, using canyons and coastal winds as natural highways. Every movement is a balance of patience and distance — the art of covering ground without wasting energy.

Diet & Hunting

California Condors are strict scavengers, relying entirely on carrion to survive. Unlike hawks or eagles that chase down live prey, condors search for what’s already fallen — the carcasses of deer, elk, bighorn sheep, cattle, or even whales washed ashore along the coast. Their eyesight is extraordinary, allowing them to spot a meal from miles away. Often they follow the cues of other scavengers, dropping in once a site is located, their size giving them dominance when competition gathers.

Their bills are massive tools of survival, long and hooked, built not for quick precision but for brute strength. With them, condors can tear through the thickest hides, opening carcasses that smaller scavengers couldn’t hope to penetrate. Once the barrier is broken, other species — vultures, ravens, even coyotes — move in to share the feast. In this way, the condor plays the role of opener, the first to make the meal accessible, setting the table for the rest of the scavenger guild.

By focusing on the largest carcasses, condors fill a niche that no other bird in North America can match. They are the cleanup crew of the high country and the coast, recycling nutrients from megafauna that would otherwise linger and rot. Each meal they take is part of an ancient cycle, a reminder that scavenging is not a lesser role but one of the most essential in any ecosystem.

Nesting & Life Cycle

California Condors reproduce at one of the slowest rates of any bird. They don’t weave stick nests in trees or on cliffs like hawks or eagles. Instead, they seek out sheltered ledges, caves, or crevices, often deep within rugged canyons or on remote cliff faces. A female lays just a single egg, and not every year — most pairs breed only once every other year, a rhythm that leaves little margin for population growth.

Incubation lasts nearly two months, with both parents sharing the duty of keeping the egg warm. Once the chick hatches, the parents feed it by regurgitation, delivering meals of carrion directly into the open bill. Growth is slow. Young condors remain in the nest for five to six months before their first flight, and even then, they are far from independent. For nearly a year afterward, fledglings shadow their parents, learning to navigate the air currents and locate food.

This long, demanding cycle is one reason condors came so close to extinction. With such a limited capacity to replace themselves, even modest losses can devastate a population. Yet it is also part of what makes them extraordinary. To watch a California Condor take wing is to see the product of half a year of careful raising — a bird built for decades of life in the sky, a survivor nurtured in one of the most ancient ways nature knows.

Sounds

California Condors are nearly silent in the sky. Like their vulture relatives, they lack a syrinx — the voice box that allows most birds to sing or scream. Because of that, their vocal range is limited to low grunts, hisses, and wheezes, usually heard only up close at feeding sites or in the nest. These sounds are more functional than dramatic, serving as warnings or quiet exchanges between adults and chicks.

That silence is part of their aura. A condor with a nine-foot wingspan can drift overhead without a sound, no call announcing its presence, no cry echoing through a canyon. Where a Red-tailed Hawk screams and an eagle whistles, the condor passes wordlessly, its shadow sliding across the rock below. It’s an eerie stillness, but fitting for a bird whose power lies not in its voice, but in its endurance and scale.

Conservation

The California Condor is one of the most dramatic conservation stories in the world. Once ranging across most of North America, their numbers collapsed in the 20th century due to habitat loss, hunting, poisoning, and especially lead fragments left in carcasses from ammunition. By 1982, only 22 individuals remained. Extinction seemed certain.

In an unprecedented move, wildlife agencies captured every remaining condor for a last-ditch captive breeding program. It was a gamble that worked. Through decades of careful management, breeding centers began producing chicks, and in the 1990s, the first young birds were released back into the wild. Today, more than 300 condors soar free in California, Arizona, Utah, and Baja California, with another 200+ held in captive breeding facilities. The species is still listed as critically endangered, but it is no longer teetering on the brink.

Cool Fact: Every California Condor alive today has been marked and monitored, meaning biologists know the history of every single bird in the population. Few species on Earth are so closely tracked.

Each bird is monitored closely but the population remains fragile. Lead poisoning continues to be a major threat, and every year some birds are treated for exposure. Yet the sight of condors circling above Grand Canyon cliffs or coastal Big Sur would have been unthinkable a few decades ago. Their survival is proof that conservation at its most ambitious can succeed.

The California Condor is more than a bird — it’s a symbol of survival. Once nearly erased from the skies, it now soars again over canyons, cliffs, and coastlines, carried by decades of relentless conservation. With wings nearly ten feet across, it is North America’s largest flying bird, and one of the rarest to encounter.

To see a condor gliding overhead is to glimpse deep time itself, a reminder of ancient skies and the fragile resilience of life. Few sights in the natural world carry more weight, or more hope.