The Turkey Vulture is one of the most widespread raptors in the Western Hemisphere. Unlike hawks or eagles that chase live prey, it thrives on carrion—nature’s recycler, built to find what others leave behind and keep the landscape clean.

- Length: 25–32 inches (64–81 cm)

- Wingspan: 5.5–6 feet (170–183 cm)

- Range: From southern Canada through the entire U.S., Central America, and deep into South America, the Turkey Vulture is among the most abundant raptors in the world.

What to Look For

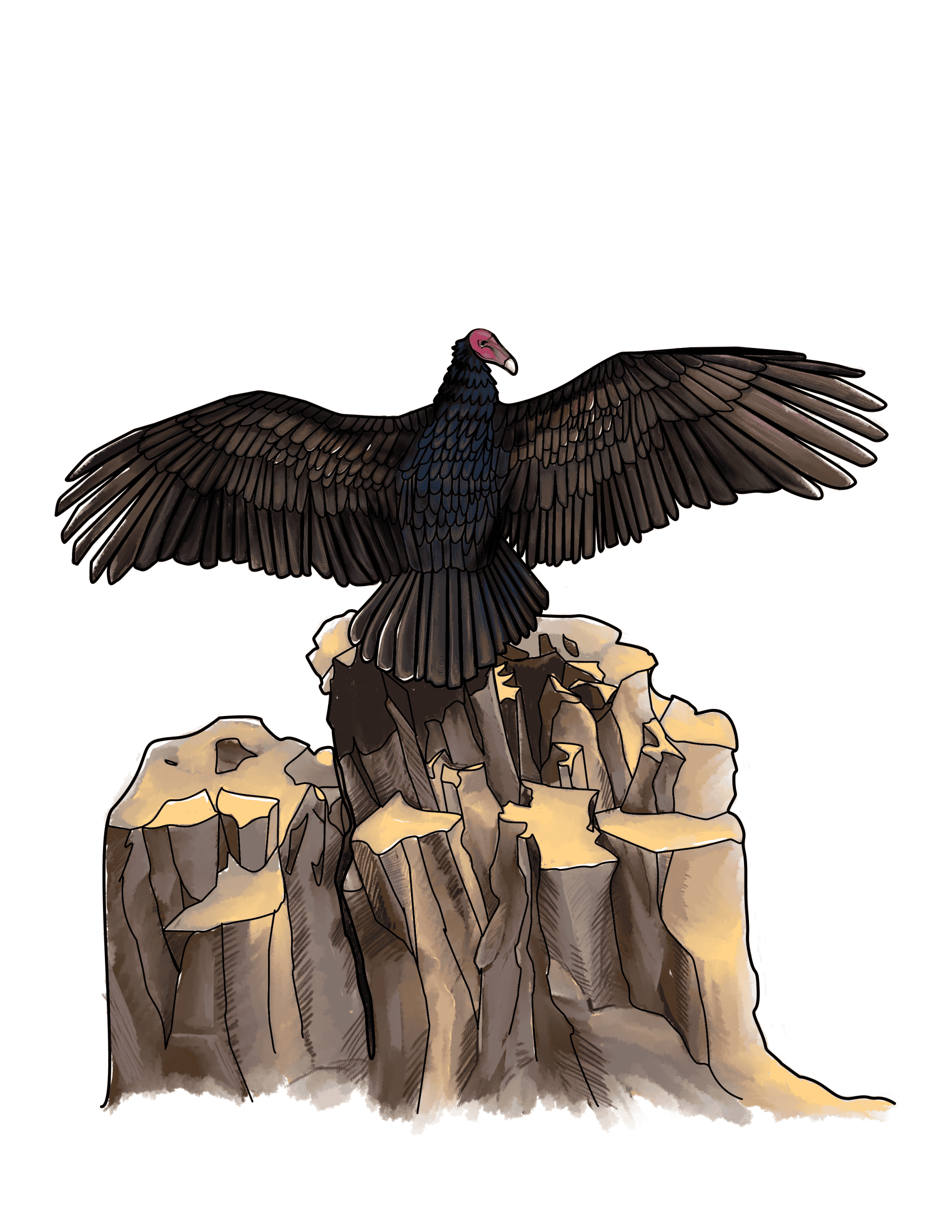

At first glance, the Turkey Vulture looks like a dark, hulking shadow overhead, but the closer you study it, the more its details come into focus. The body is cloaked in chocolate-brown to black feathers that can flash bronze or greenish in the sun, giving a surprising sheen to a bird often thought of as drab. The head, by contrast, is bare skin — a small, wrinkled patch of bright red on adults, pinkish on juveniles. It may not look elegant, but it’s perfectly suited for a bird that spends its life with its face in carrion, keeping the feathers clean where it matters most.

The wings are the real giveaway. Turkey Vultures carry long, broad wings that show a striking two-tone pattern in flight: dark along the leading edge, pale gray along the trailing half. Against a bright sky, that contrast jumps out, a quick visual cue for anyone learning to tell vultures from eagles or hawks. Add the tail — long and rounded — and the outline begins to take shape.

But perhaps the most unmistakable feature is how they fly. Turkey Vultures rarely flap for long. Instead, they hold their wings in a shallow “V” — a dihedral posture — and drift with an easy, unsteady grace. They rock side to side as the air pushes against them, a loose, tilting flight that seems almost sloppy compared to the steady circles of a hawk or the rigid glide of an eagle. Once you know that rocking, wobbly style, it becomes a signature. Spot a large dark bird see-sawing across the sky, and chances are high you’re looking at a Turkey Vulture.

Behavior & Flight Style

Turkey Vultures are creatures of the air, and they make it look easy. With wings nearly six feet across, they are masters of soaring, rarely flapping unless forced. On warm days, they catch rising thermals and spiral upward in lazy circles, climbing higher and higher with no more effort than a tilt of the wing. From below, the rocking glide becomes their trademark — that side-to-side wobble is as diagnostic as their bare red head. What looks unstable is actually efficiency, a way to fine-tune balance as they ride invisible rivers of air for miles at a time.

The contrast between ground and sky could not be sharper. Perched or walking, Turkey Vultures can look awkward, almost comical, shuffling with a hunched posture and heavy steps. But once airborne, the transformation is striking. They become graceful drifters, covering vast distances with an ease that outpaces most raptors. Their flight is built not for speed or attack but for endurance, a roaming search across the landscape for the scent of death on the wind.

One behavior makes them especially iconic: the sunbath. On cool mornings or after a meal, Turkey Vultures will spread their wings wide, feathers splayed, holding a crucifix pose as they face the light. Scientists suggest it serves multiple purposes — drying feathers, warming the body, even baking bacteria from their plumage after hours spent feeding. Whatever the reason, the sight of a vulture perched on a snag, wings stretched like a dark banner against the sun, is one of the most unforgettable postures in the bird world.

Diet & Hunting

Turkey Vultures are not hunters in the traditional sense. They don’t stoop from the sky like eagles or hover and dive like ospreys. Instead, they specialize in what’s already gone — carrion. And in that niche, they are unmatched. Their sense of smell is among the most acute in the bird world. Where most raptors rely on sight alone, Turkey Vultures can detect the faint odor of ethyl mercaptan — the gas released by decaying flesh — from over a mile away. In dense forests or rolling hills, they’ll glide low, letting scent guide them to the unseen. It’s an ability so refined that even natural gas companies once studied them, since vultures could locate leaks by mistaking the odor for food.

That bare, wrinkled red head, so often the punchline of jokes, is actually perfect survival engineering. Feathers would only foul with bacteria and rot when reaching deep inside carcasses. Bare skin, by contrast, is easy to keep clean and resistant to infection. Add in their habit of sunbathing with wings spread wide, and you have a bird designed to sanitize itself after even the messiest meal.

By consuming the dead, Turkey Vultures serve a role few other animals can fill. They recycle nutrients locked in carcasses and reduce the spread of disease by cleaning up what would otherwise fester. What seems grotesque is actually essential — a form of natural sanitation that benefits every creature sharing their range. Without vultures, landscapes would be littered with decay. With them, the cycle of life runs cleaner, quieter, and far more efficiently.

Migration & Range

Turkey Vultures are partial migrants, and their movements depend on geography. In the northern U.S. and across Canada, most birds leave when winter sets in, heading south in search of open ground and available food. The journey is one of the great autumn spectacles: spiraling kettles of vultures rising on thermals, sometimes hundreds strong, drifting together across ridgelines and valleys. To watch one of these migrating flocks is to see the sky itself in motion, dark specks circling higher and higher until they stream southward in loose formation.

Farther south, the story changes. In the southern U.S., Mexico, and much of Central and South America, Turkey Vultures are year-round residents. Mild climates and a constant supply of carrion mean there’s no need to move. In these regions, the familiar rocking glide is a fixture of the landscape in every season, just as common over a tropical rainforest as it is above a desert canyon.

Their range is enormous — one of the widest of any raptor on earth. From Canadian forests to Patagonian cliffs, Turkey Vultures span nearly an entire hemisphere. Few other birds of prey are so versatile, able to thrive in such a sweep of habitats. Whether kettling by the hundreds over mountain ridges or drifting alone above a rural highway, they remain one of the most familiar silhouettes in the Americas.

Nesting & Life Cycle

Turkey Vultures break the mold when it comes to raptor nesting. While hawks and eagles pile sticks high into trees or cliffs, vultures skip the architecture entirely. They prefer the ready-made shelter of caves, hollow trees, abandoned buildings, or even a patch of ground tucked beneath dense cover. There’s no weaving, no construction — just a simple, hidden spot to keep the eggs safe. The strategy is less about show and more about survival, perfectly in step with a bird that makes a living from what others leave behind.

Clutches usually number one to three eggs, pale and blotched, laid on bare surfaces without much lining. Both parents take turns with incubation, sharing the quiet duty of keeping the eggs warm. When the chicks hatch, they are downy and awkward, relying completely on the adults. Meals arrive in the form of regurgitated carrion, delivered straight from the parent’s crop. It may sound unappetizing, but for a growing vulture, it’s the perfect diet.

Growth is steady, and by ten to eleven weeks the young are stretching their wings and ready to launch. Their first flights may be clumsy, but instinct carries them upward, and soon they are drifting alongside the adults. From that point on, they join the endless soar — a life spent more in the sky than on the ground, carried forward by thermals and guided by scent.

Sounds

Turkey Vultures are quiet by design. Unlike hawks or eagles, they lack a syrinx — the complex voice box that gives most birds their range of calls. As a result, they don’t scream, whistle, or chatter. Instead, their vocalizations are limited to hisses and low grunts, usually given up close when defending a carcass, bickering at a roost, or warning off intruders near a nest. The sounds are guttural and rough, more like the rasp of an animal than the cry of a bird.

That absence of a true call gives them an eerie presence in flight. To see a bird with nearly a six-foot wingspan glide silently overhead, rocking on the thermals without a sound, is to understand part of their mystique. Where a Red-tailed Hawk announces itself with a scream, the vulture passes without a word, leaving only the shadow sliding across the ground. In a way, their silence suits them perfectly — patient, efficient scavengers whose presence is felt more than it is heard.

Conservation

For all their macabre associations, Turkey Vultures are a conservation success story. Across their vast range, populations are stable or even increasing, a testament to their adaptability. They are masters of efficiency, able to soar for hours with barely a wingbeat, riding thermals with an ease that few other raptors can match.

They also come equipped with some unusual survival strategies. Turkey Vultures are one of the few birds to practice urohidrosis — cooling themselves by defecating on their legs, the evaporation lowering body temperature on hot days. It’s not pretty, but it works. Inside, their biology is just as remarkable. Their stomach acid is strong enough to neutralize anthrax, botulism, and even rabies pathogens, making them frontline disease-control agents every time they feed on a carcass.

Cool Fact: When threatened, Turkey Vultures vomit. The foul-smelling slurry not only repels predators but also lightens their body for a faster getaway. It’s grotesque, yes — but brilliantly effective.

The Turkey Vulture is proof that beauty isn’t always the measure of importance. They may not have the majesty of an eagle or the speed of a falcon, but their resilience and efficiency keep the natural world in balance. Every carcass consumed is disease contained, every effortless mile of soaring a reminder of nature’s quiet engineering.

The next time you see one rocking overhead on broad wings, remember — this is the bird holding the landscape together, silently and without fanfare.